The New England Journal of Medicine took the unprecedented step of not only publishing the SPRINT trial on hypertension but also adding 2 editorials, a perspective and a clinical decision article on treatment of hypertension in the same issue, along side the original article.The message is resounding; we now have a large randomised study documenting lowering of systolic blood pressure in a hypertensive population reduces clinical outcomes.

The researchers randomized 9361 persons with systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or higher and increased cardiovascular risk (but without diabetes) to a systolic pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg (intensive treatment) or to standard treatment of a target less than 140 mm Hg. The primary composite outcomes were myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, heart failure, cardiovascular death or other acute coronary syndromes.

After a period of 1 year, the mean systolic blood pressure achieved in the intensive treated group was 121.4 mm Hg and 136.2 mmHg in the standard treatment group. The study was stopped prematurely after a median follow-up of 3.26 years due to significant reduction in rate of composite outcomes in the intensive treatment cohort (1.7% vs. 2.2% per year, P<0.001); a 25% relative reduction. The numbers needed to prevent death from any cause and death from cardiovascular causes, during 3.26 years of the trial, were 90 and 172. Myocardial infarction was reduced from 2.5% to 2.1% (P=0.19); stroke was lowered from 1.5% to 1.3% (P=0.50);heart failure was brought down from 2.1% to 1.3% (P=0.002); cardiovascular death was reduced from 1.4% to 0.8%(P=0.005); there was no reduction in acute coronary syndrome (0.9% vs. 0.9%; P=0.99). The absolute reductions in clinical outcomes are by no stretch of imagination something to write home about. There was insignificant reduction in myocardial infarction and stroke, and in fact no reduction at all in acute coronary syndrome. The primary outcome (the first occurrence of myocardial infarction,acute coronary syndrome,stroke,heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes) was reduced a mere 1.6%, from 6.8% to 5.2% after providing treatment for over 3 years. Standard or usual anti-hypertension treatment ( targeting systolic pressure below 140 mm Hg) for 3 years resulted in 1.4% cardiovascular deaths , or in other words 98.6% elderly patients with cardiovascular risks were still alive after 3 years.

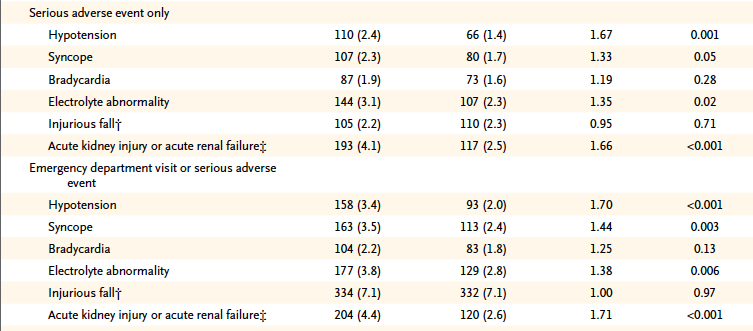

However improved clinical outcomes achieved with intensive lowering of blood pressure came at a significant price. Hypotension was significantly increased by 67%, syncope significantly increased by 44 %, electrolyte abnormality significantly increased by 38 % and acute kidney injury or acute renal failure by a significant 71%. There was however no significant increase in orthostatic hypotension. We must note that the populations studied by the SPRINT researchers were all more than 50 years , and 25% were older than 75 years. Increased cardiovascular risk was defined by one or more of the following: clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease other than stroke, chronic kidney disease excluding polycystic kidney disease, a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 15% or greater, or an age greater than 75 years. Patients with prior stroke or diabetes were excluded. Patients were provided all major classes of anti-hypertensive medicines, but use of diuretics was encouraged as first line agent. Chorthalidone was recommended as the diuretic and amlodipine as the preferred calcium channel blocker. Dose adjustment was made on a mean of 3 blood pressure measurements with an automatic apparatus after 5 minutes of rest in the office.

We are yet again faced with the dilemma of seemingly impressive relative gains with an intervention but minimal absolute differences. The SPRINT investigators provide Table 3 that documents increased emergency department visits by 70% due to hypotension (2.0% to 3.4%; P<0.001) and acute renal failure by a significant 71% (2.6% to 4.4%; P<0.001). One shall have to be wary of lowering systolic blood pressure to 120 mm Hg with such rates of serious adverse effects in elderly patients. I wonder why the hoopla over this trial whose data clearly is unable to outweigh safety by benefits.

The New York Times and other mainstream media need to reassess their initial excitement over the SPRINT trial publicity campaign. I certainly would not treat 170 patients for more than 3 years to obtain a systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg at the expense of acute kidney failure or clinical hypotension mandating a visit to the casualty of a hospital.

The Eight Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines published in late 2013 recommended a target of 150/90, for people above 60 years and 140/90 mm Hg for every one else. There have been comments made by distinguished cardiologists that the SPRINT data would modify the JNC 8 target blood pressure guideline targets. I however differ; particularly with the knowledge that the Cochrane Collaboration’s Hypertension Group’s review on treatment of mild hypertension showed no evidence that drugs benefit patients. Almost 11% patients on the contrary , developed enough side effects to compel them to stop treatment.

Treatment cost (based on data from the American Heart Association’s Heart Disease and Stroke Update ) for medicines and office visits for approximately 22 million Americans (in 2013) with mild hypertension was estimated at 32 $ billion. It is also estimated that 10 years of mild hypertension treatment alone would provide a bill of 400$ billion. The president of the American Society of Hypertension, Dr. William White declared that the conclusions by the Cochrane Review were “flawed” and “had no clinical importance”. He also went on record to state that the review “should not be adopted by any practicing physician.” Dr. White it should be pointed out had financial relationships with 15 drug companies manufacturing anti-hypertensive drugs.

Millions of people would have to endure hypotension, faints, acute kidney failure, impotence, dizziness, light-headedness and even falls severe enough break a hip without substantial benefits if senior citizens are forced to lower their systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg. Strictly speaking, comparing mild hypertension treatment with data from the SPRINT trial may not be appropriate but the prospect of fiscal bonanza for drug companies cannot be over-estimated.

It would be prudent not to trigger acute kidney failure or faints in elderly patients of hypertension by insisting on lowering their blood pressure to 120 mm Hg armed with the knowledge that standard treatment with target blood pressure in the 130’s permitted almost 99% of patients to be alive after 3 years.