A recent paper addressing etiology of sudden death in sports has been published by JACC (2016;67:2018-15) against the background that accurate knowledge of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in athletes and its precipitating factors is necessary to establish preventive strategies. Data is provided from a United Kingdom regional registry. The study investigated causes of SCD and their association with intense physical activity in a large cohort of athletes. The study includes 357 consecutive cases (mean age 29 years, males 92%, Caucasian 76%, competitive 69%), who underwent detailed post-mortem evaluation, including histological analysis by an expert cardiac pathologist.

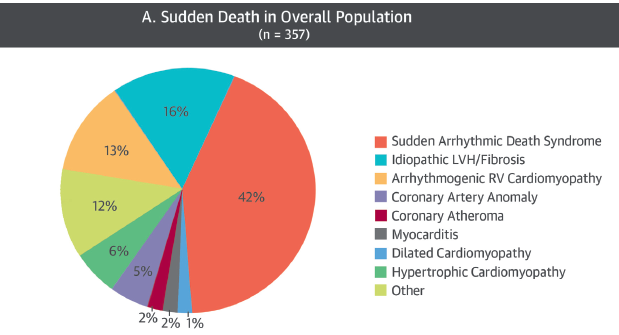

The most prevalent cause of death was sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS), which accounted for 149 deaths (42%). Myocardial disease was detected in 40% of cases, including idiopathic left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and/or fibrosis (n=59,16%); arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy (AVRC) (13%); and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (6%). Coronary anomalies occurred in 5% of cases. SADS and coronary anomalies affected predominantly young athletes (<35 years of age), while myocardial disease was more common in older individuals. Left ventricular fibrosis and AVRC most strongly predicted SCD during exertion and SCD during intense exercise occurred in 61% of cases. Therefore almost 40% of athletes died during rest, underscoring the need for further preventive strategies.

Sudden cardiac death in a young athlete (<35 years) is a tragic event and so far most reports regarding the cause of SCD in athletes are limited by the lack of detailed post-mortem examination performed by a an experienced cardiac pathologist. There could be as much as 40% disparity in result between a referring pathologist and a specialist cardiac pathologist, with respect to cause of death.

The UK study has revealed that a normal heart indicative of an arrhythmic death was present in a significant proportion of athletes. A structurally normal heart accounted for 42% of the overall cohort, and SADS has also been incriminated in US studies (31% in college students and 41% in young soldiers).

Idiopathic LVH and/or fibrosis and AVRS were the predominant causes of myocardial disease seen in 40% of the autopsies. The entity of idiopathic LVH is as yet unclear. Idiopathic LVH may be an innocent bystander or may be a variant of HCM, particularly in the presence of LV fibrosis. Idiopathic LVH could be a trigger for arrhythmia in SADS. In this study HCM accounted for only 6% of deaths. The present study demanded that for a diagnosis of HCM to be made there should be >20% of myocardial disarray in at least 2 tissue blocks of 4 cm2. Most other studies have maintained HCM as the commonest cause of SCD in athletes because of less stringent pathological criteria for diagnosis of HCM.

Almost 8% of autopsies showed idiopathic fibrosis. Possible explanations could be healed myocarditis or incomplete expression of cardiomyopathy. Maybe long standing intense exercise may be a causal factor. Raised biomarkers indicative of myocardial injury have been reported post endurance events, and increased prevalence of myocardial fibrosis on cardiac MRI has been seen in veteran endurance athletes.

Sudden arrhythmic deaths accounted for half of deaths in children and adolescents but for only 26% of deaths in individuals >35 years. Myocardial disease was more common in older people. ARVC was the cause of death in 18% of people >35 years. Autopsy series of deaths due to ARVC have revealed that almost 40% of deaths occurred after age 35 years.

The strongest predictor for SCD during exercise was ARVC. Athletes with ARVC were 6 times more likely to die on exertion compared to other cardiac pathologies. Left ventricle fibrosis was also an independent predictor of exercise-induced SCD.

Almost 40% of deaths were at rest with 13% during sleep. Most of these deaths were due to arrhythmias and hence a 12 lead ECG may be able to pick up most of the channellopathies. ECG has also been seen to be abnormal I 55% to 75% of ARVC and therefore people with this disease may also be identified. The researchers of the British study conclude that because of the high prevalence of idiopathic LV fibrosis/LVH there is need for further studies in the field to delineate their significance.

What about the role of preparticipation screening of young athletes? The recent article by Van Brabandt and colleagues presents a detailed review of screening in young athletes and have elicited an editorial in the BMJ (BMJ 2016, published 20 April 2016). The paper concluded that screening in athletes should be abandoned for several reasons, including the rarity of SCD in this group, the high rate of false positive results, and lack of robust evidence that it works. They argue that SCD in athletes is very rare (1 in 80,000 athletes a year and basic cost-benefit analyses suggest that 33,000 athletes would need to be screened to save one life at a cost of $1.32 million. The high rate of false positive results means athletes need further investigation, with the possibility that the tests fail to resolve whether they have an underlying disease. This could lead to healthy asymptomatic people being excluded form sport unnecessarily. A randomized controlled trial comparing pre-participation screening with no screening would a long-term costly trial because of the rarity of SCD in athletes. The 12 lead ECG was made a paramount screening tool after a 26 year study that reported an 89% decrease in SCD with screening by ECG from the Vaneto region of Italy. However the study was retrospective, with small number of events, and controversy remains over the baseline prescreening of events (JAMA 2006,296:1593-601).

.

In Italy pre-particiatory screening in competitive sports has been mandatory since the 1970’s. In Holland, however, required screening was stopped in 1984 due to concern over the effectiveness of the tests. There is no wide spread screening, but the American Heart Association recommends that athletes get a physical exam have their personal and family medical history taken. A new consensus statement released about cardiovascular care of college athletes does not for or against ECG screening, it offers best practices for those organizations that want to implement it. According to the Van Brabandt data current research does not offer solid evidence that screening prevents deaths and in fact indicates that 25% of people with a condition that could lead to sudden death would not be identified by a screening for a sensitivity of 0.75. Of 115 young athletes who died of SCD and had undergone pre-participation screening, only 4 had showed some evidence of possible heart disease at time of screening, and only 1 athlete had the cardiac abnormality that led to death correctly identified.

However instead of launching a prohibitively expensive screening program across the country it would be worthwhile doing ECG’s in only those competitive athletes attending a particular stadium or gym. Education may also have a role in preventing sudden death in athletes. Awareness must be increased among health care professionals such as the primary physician. Recognition of important red flags such as unexplained syncope, or a family history of sudden death or heart disease may warrant referral to a cardiologist for further assessment. Moreover all coaches and athletes should receive CPR training and automatic external defibrillators should be present in all sporting avenues/gyms.